Ente di Colonizzazione del Latifondo Siciliano (ECLS, Entity of Colonization of Sicilian Latifundia), 1940-1943

In 1940, the fascist regime established the Ente di Colonizzazione del Latifondo Siciliano (ECLS, Entity of Colonization of Sicilian Latifundia), following the model of the “Entity of Colonization of Libya” and what had already been experimented with the plans of integral land reclamation of the Pontine Marshes around Rome. Sicily represented the last front of an “internal colonization” process aiming at the “repopulation” and “modernization,” i.e. occupation and forced urbanization, of territories perceived as "empty" and "underdeveloped" homogeneous geographical spaces.

The plan was to build a network of sixteen villages to guide the agricultural transformation of the Sicilian countryside adopting an extensive, extractive, and capitalist approach, but also to allow the regime to carry on forced migration plans to the South in order to prevent uprisings in the northern countryside and sever ties between agricultural workers and anti- fascist movements. Despite these premises, as Italy entered the Second World War in 1940, an early break in the works came in 1943. Only eight of the envisioned sixteen villages were inaugurated until then, while the others remained unfinished.

Following the principles of modernist aesthetics and the plans of fascist colonial architecture, the villages were built around the void of the square, the “civic center” surrounded by the State institutions designated to forge the cultural, political, and spiritual education of “the fascist of tomorrow”: the Casa del Fascio (House of the National Fascist Party), the Church, the School, the Entity of Colonization, etc.

The depopulation of the Sicilian countryside following the war led to the abandonment of most of these villages and to the deterioration of their buildings, some of which have been repurposed by residents as homes. In recent years, the right-wing Sicilian regional government, in an attempt to rehabilitate fascist policies, has allocated funding for the architectural preservation of these settlements, restoring them to their original state. Aligned with modern architectural history and restoration theories separating aesthetics from social, political, and economic values, these conservation efforts reinforced the idea that fascist architecture can exist without perpetuating fascist ideologies.

Despite the fall of fascism and the end of historical colonialism, Italy’s process of de-fascistization and decolonization remains unfinished. To date, the absence of a critical review process has allowed the cultural and political legacy of colonialism and fascism to persist in institutional racism, but also in a dearth of education regarding Italy's violent history and in the unquestioned, normalized, or neglected permanence of numerous buildings, monuments, memorials, plaques, and toponyms embodying and celebrating it.

Considering the resurgence of fascist ideologies on a global scale and the unignorable migratory movements from former colonies to Europe especially, re-opening a process of decolonization and de-fascitization in Italy has become more urgent than ever. Also, we need to finally address the question of what to do with the architectural heritage of fascism and colonialism. Is it possible to repurpose it without perpetuating the ideologies expressed by it, while also guarding against the risks of self-absolution and nostalgia? Who holds the right to preserve, reuse, and re-narrate this heritage?

Verso un Ente di Decolonizzazione / Towards a Decolonization Entity, 2017-2021

In 2017, Asmara was designed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site under the title “Asmara, a Modernist City of Africa,” referring to the architectural and urban transformation associated with the Italian colonial occupation of Eritrea. Subjected to various criticisms, the nomination of Asmara has raised many concerns, primarily about the risk of presenting the city built by the Italian settlers as a model of urban heritage for the African continent, while also denouncing the Eurocentric perspective of architecture underlying the conservation paradigms enforced by UNESCO.

We must acknowledge the interconnectedness of colonialism and modernism. Architectural modernism continues to be celebrated for its aesthetics, regardless of its colonial foundations, and it is at the foundation of a modern conception of architecture and urban planning that is still embraced by many. Modernism and its conception of modernity are inherently connected to the dismissal and degradation of other approaches and worldviews. Consequently, in the name of modern architecture, entire communities, ways of life, and historical landmarks are erased. Postmodernism has already attempted a critique of modernism, but a critique alone is insufficient. Our task is to imagine architectural forms that go beyond modernism, towards demodernization.

Demodernization as explored in the work of DAAR is not an anti-technological, reactionary anti-modernism, and it does not align with any nationalist and fascist nostalgia. Instead, it involves the “profanation” of modernist architecture as a method of desegregation, operating as both discourse and praxis, contrasting modernity's aggressive universalism and alienation, inventing forms of re-appropriation and re-use.

Verso un Ente di Decolonizzazione / Towards a Decolonization Entity is the art installation presented by DAAR at Palazzo delle Esposizioni in Rome—which hosted the first international exhibition of colonial art in 1931—for the 2020 Rome Quadrennial FUORI, curated by Sarah Cosulich and Stefano Collicelli Cagol. Taking inspiration from the designation of Asmara as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the installation reconsiders the history of the fascist villages built in Sicily as a preliminary step towards the creation of a Entity of Decolonization for those who feel the need to question the historical, cultural, and political legacy of a history imbued with colonialism and fascism.

In the summer of 2021, DAAR organized the Difficult Heritage summer school in Borgo Rizza, one of the aforementioned rural settlements of the fascist regime. Like the others, this village was named after a “fascist martyr,” of which we strike out the name to reject his commemoration and instead remember his actions as a war criminal. Against a backdrop of nostalgic and neo-fascist sentiments exemplified, for instance, by the recent installation of a new plaque in Borgo Bonsignore commemorating the heroic gestures, i.e. the crimes against humanity, of a General who died during the occupation of Ethiopia, DAAR collaborated with the Municipality of Carlentini, the local community, the Royal Institute of Art in Stockholm, and the University of Basel to open up a space for critical pedagogy, to investigate the aftermath of colonial and fascist architectural heritage.

The summer school explored possible new relationships with this troublesome heritage, while problematizing the exploitative dynamic between “urban” and “rural” areas, but also migration histories and lingering issues of post/colonial injustice, especially in the light of a renewed interest in the “countryside” during the COVID-19 pandemic. Moving one step forwards toward a Entity of Decolonization, the summer school also represented a first, important act of profanation of these sites, used against themselves, opened up for new common uses different from those they were designed for.

Ente di Decolonizzazione – Borgo Rizza / Entity of Decolonization – Borgo Rizza, 2022-2024

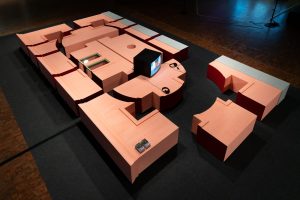

Continuing the profanation of the Entity of Colonization of Sicilian Latifundia, both on a physical and a symbolic level, the installation Ente di Decolonizzazione – Borgo Rizza / Entity of Decolonization – Borgo Rizza expands the conversation about Italy’s process of de-fascistization and decolonization into other contexts, fostering dialogues with other sites and communities, building new alliances.

Based on the facade of the Entity of Colonization in Borgo Rizza, deconstructed into multiple modules remanufactured as modular seats to form the platform for an open discursive space, the art installation was moved and reassembled in different contexts sharing with Borgo Rizza a particularly favorable position for addressing questions of decolonization and de-fascistization. Preceded by open invitation letters, the activations of the installation were intended as “decolonial assemblies,” welcoming everybody willing to take part in this conversation. Participants were encouraged to share personal experiences, reflections, or uncertainties regarding their relationship with the legacies of fascism, colonialism, and modernism, coming together in a horizontal space open to vulnerability, to imagine new possibilities of critical use of this physical and symbolic colonial heritage.

This website features partial transcripts from the “decolonial assemblies,” punctuated by questions that were born out of these conversations, as guidelines for a collective process of decolonization.

Ente di Decolonizzazione – Borgo Rizza / Entity of Decolonization – Borgo Rizza

A project by DAAR – Sandi Hilal and Alessandro Petti

Research: Sandi Hilal, Emilio Distretti, Alessandro Petti

Project Coordinator: Sara Pellegrini

Public Program Curator: Matteo Lucchetti

Installation Design Assistance and Executive Production: Orizzontale and Zapoi

Video Editing: Husam Abusalem

Documentation: Pietro Onofri

Website Design: Elisa Chieruzzi, NERO Editions

Online Platform Editors: Michele Angiletta and Marta Ceccarelli, NERO Editions

Website Development: Emanuele Pesa

Acknowledgments: Corrado Gugliotta, Salvatore La Rosa, Iole Lianza, Laura Mariano, Remo Minopoli, Nicolò Stabile, Kathryn Weir

Co-commissioned and co-produced by La Loge, Brussels; Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art; Madre Museum, Naples; and the Municipality of Albissola Marina

Project supported by the Italian Council (10th Edition, 2022), program to promote Italian contemporary art in the world by the Directorate-General for Contemporary Creativity for the Italian Ministry of Culture

Material: wood, plaster, plexiglass

Dimensions: 350x600x45 cm

Courtesy the artists